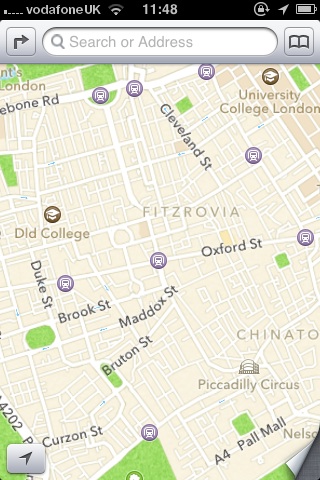

Urban Navigation

Many of us trying to negotiate the labyrinthine streets of large cities have become reliant on the GPS and map function of our smart phones, or else stopping to ask for directions. But what tricks could you use to find your way around a deserted post-apocalyptic urban area if you don’t have these options – perhaps getting lost on a scavenging foray, or becoming disorientated while trying to escape a spot of bother. There are a few really handy pointers you can use for urban exploration.

Many of us trying to negotiate the labyrinthine streets of large cities have become reliant on the GPS and map function of our smart phones, or else stopping to ask for directions. But what tricks could you use to find your way around a deserted post-apocalyptic urban area if you don’t have these options – perhaps getting lost on a scavenging foray, or becoming disorientated while trying to escape a spot of bother. There are a few really handy pointers you can use for urban exploration.

It is perhaps a commonly-known element of woodsman’s lore that if you lose your bearings you can look to the moss growing on tree trunks. Moss thrives preferentially in cooler, damper sites protected from direct sunlight, which in northern latitudes means on the northern side of trees (and visa versa in the southern hemisphere). You can use a similar rule-of-thumb for picking out a general compass point in urban areas. The facade of buildings become stained and marked by pollution, and particularly by acid rain (even without industrial pollution, rainwater is mildly acidic from carbon dioxide it absorbs from the air). These are carried by the wind, and so the side of a building facing into the direction of the prevailing wind will be more exposed and so show more pollution marks. In a post-apocalyptic world, this would be all the more noticeable as the cityscape will no longer be being cleaned and restored (and you may also be able to employ the moss trick even in built-up areas). In the UK, for example, the prevailing wind direction is south-westerly, and so the side of buildings facing the south-west will show greatest signs of weathering. Be aware, though, that you can get unpredictable air flow patterns and eddies down city streets and so these prevailing wind signs may be more confused around large buildings.

Another trick you can take advantage of, particularly in residential areas, is to start taking notice of the eye-sore features sprouting out of so many apartment blocks: satellite dishes. Satellite TV is beamed back down to the Earth by a ring of communication satellites that occupy a very particular tract around the planet – geostationary orbit. If you place a satellite around 36,000 km above the equator of the Earth each orbit take 24 hours – the same time the planet takes to spin on its own axis. Such satellites remain geostationary and so hold their position above the same place on the Earth’s surface, which makes them ideal for communication relays as you can keep your radio dish pointing at the same point in the sky. If you look at a satellite dish it will be pointing towards the equator, which means in a generally southerly direction for Europe, the US, and other places in the northern hemisphere (and visa versa for Australia and other southern hemisphere locales). So you can use satellite dishes like a modern moss-on-trees directional clue.

Do be aware, though, that the dishes are unlikely to be pointing due south. Although the TV satellites will be hovering above the waistline of the world, they could still be some distance east or west of you. For example, satellite dishes picking up the Sky channel in the UK all point 28° to the east of due south (i.e. a bearing of 152°). In a more extreme case, a dish fixed to the side of an apartment block in an American city might be targeted for a European satellite channel, and so would be pointing far further round to the east. Also, this particular rule-of-thumb is not much use to you in an equatorial city as the dishes will be pointing almost directly upwards. But as a general guideline, glancing up at satellite dishes isn’t a bad way of judging south and navigating around an urban jungle by dead reckoning.

But by far the most accurate means for finding your bearings, whether in a city or rural area, is to call upon the same skills mariners have been using to navigate for millennia. The sun, of course, rises in the east and sets in the west, so knowing approximately the local time you can always get a rough feel for the compass points. There are also architectural clues to this – Christian churches are always built along an east-west line, with the altar at the eastern end to face the sunrise. Graves are also often orientated lengthwise along an east-west transect, the headstone at the east end.

More precisely, if you have an analogue watch or clock – one with a clockface rather than digital display – that is correct to local time you can use it find the compass points (the directions here are for the northern hemisphere again). Hold the watch flat and turn it round so that hour hand points towards the sun. Imagine bisecting (cutting in half) the angle between the hour hand and 12 o-clock – this is the north-south line, with north being the side opposite the sun. If you retrieve a stopped clock, you can always wind it up and set it to local time by watching the shadow of an upright stick (essentially a primitive sundial). As the shadow sweeps through due north, and shrinks to its shortest reach, this is the moment of local noon.

And after sunset in a dark post-apocalyptic city untroubled by street lamps and light pollution you’ll have no trouble in picking out the stars overhead. Familiarise yourself with the very basics of recognising Ursa Major and the pole star (Polaris) and the Southern Cross and you’ll never struggle to find true north or south in either hemisphere of the world. (Although, see Chapter 12 of The Knowledge, which discusses how these celestial poles will wander over time)

For a few different tips, see this piece by Tristan Gooley on the BBC News magazine